In Bach’s Goldberg Variations, every third variation is a canon at an increasing interval. The first (Variation 3) is at the unison (the canonic voice repeats the leading voice verbatim), the second (Variation 6) is at the second (the response repeats the subject a diatonic second away), and so on until Variation 27, which is a canon at the ninth. (Variation 30, the last of the set, where you would expect a canon at the tenth, is instead a Quodlibet).

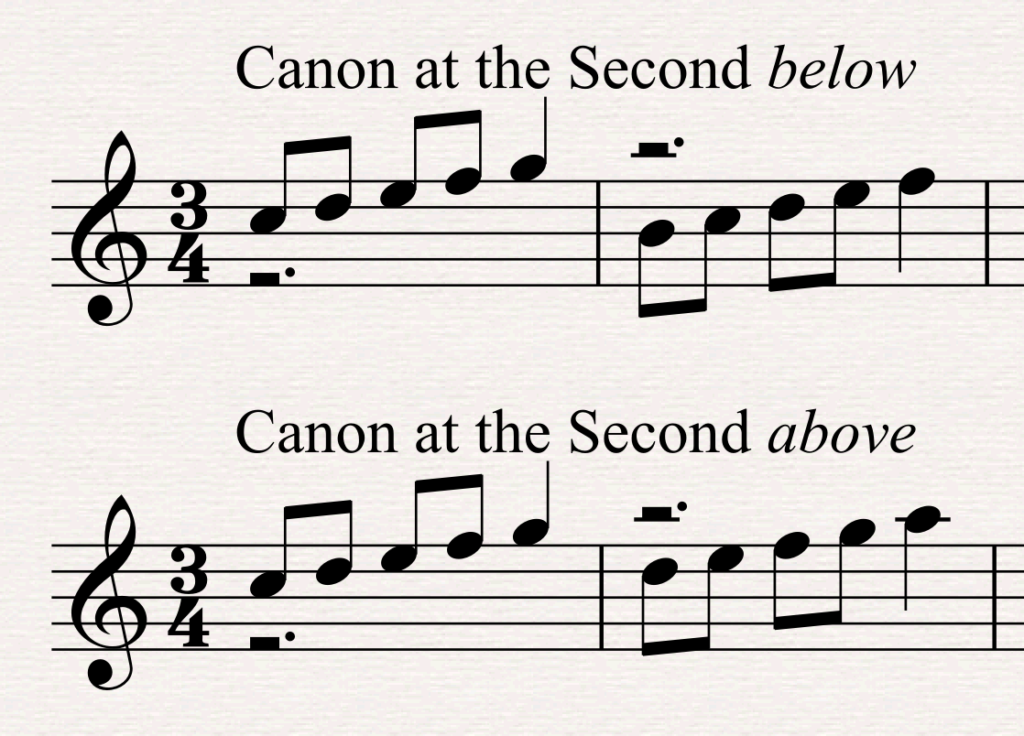

But this leaves a question: what direction does the interval in each of the canons go? If Bach writes a “Canon at the Second,” there’s some crucial information missing, isn’t there? Is it a second above? Or below?

One might expect that Bach settled on one direction, and that all of his canons are at increasing intervals above, or below. This isn’t the case. The direction of the canons, in fact, keeps changing, and seems to be an important structural component of the Goldbergs. This is something I’ve been fascinated by for a while, and I haven’t seen it discussed anywhere else before. Let’s take a look:

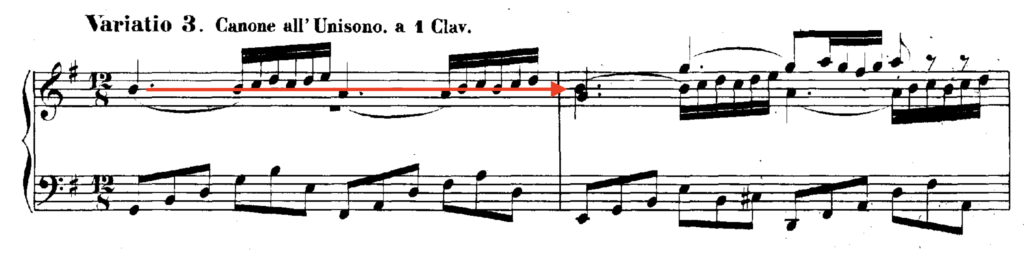

Canon #1, Var 3: Canon at the Unison —> no direction

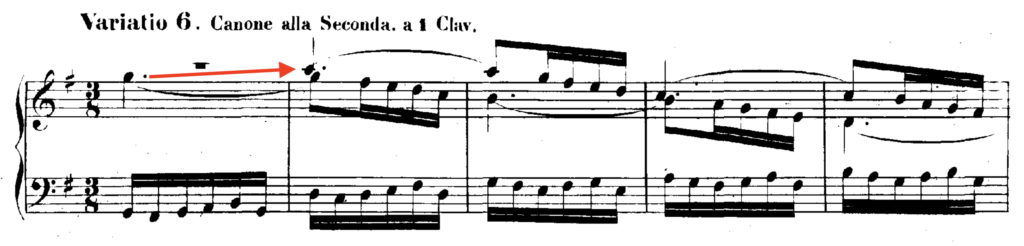

Canon #2, Var 6: Canon at the Second —> above

Canon #3, Var 9: Canon at the Third —> below

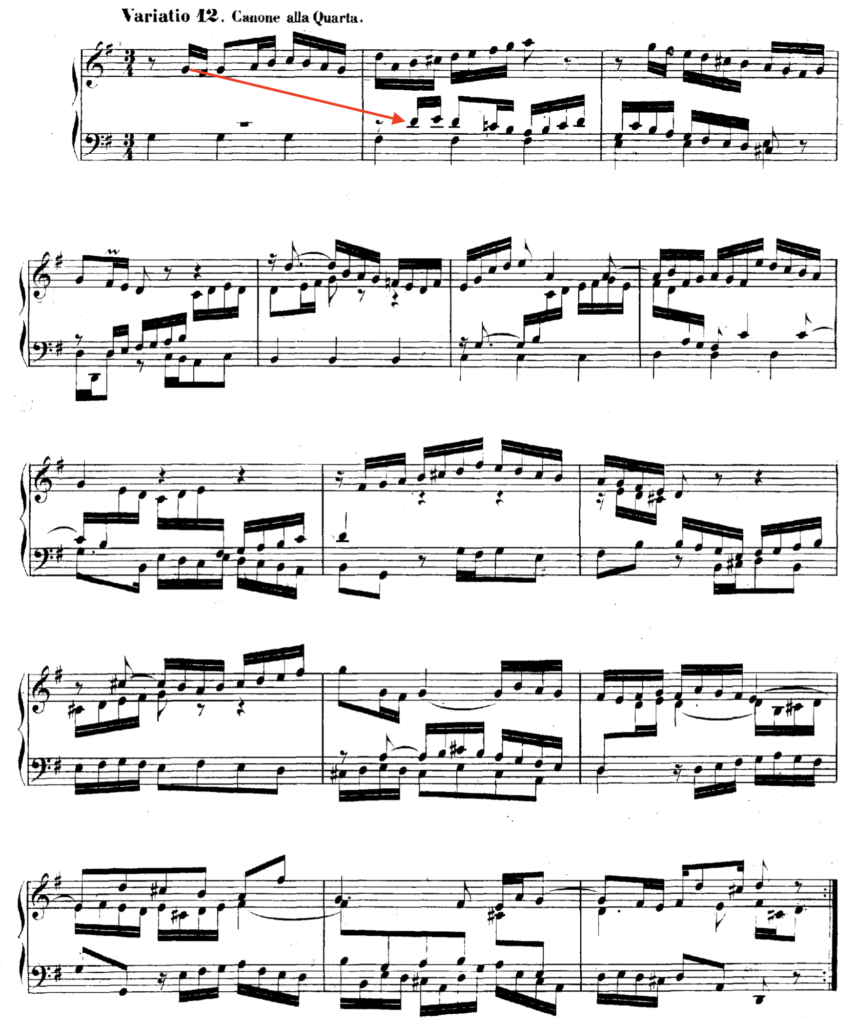

Canon #4, Var 12: Inverted canon at the fourth, with the axis of symmetry between the F and E above middle C, so that the G above middle C is transformed to the D above middle C, a fourth below. With this kind of canon, one can’t really talk about it being above or below, because anything written below the axis will have a response above it, and vice versa. However, simply because of where Bach decides to place the subject, in the 1st half, the subject is above the response, and in the second half, the subject is below the response. So I would rate this one as a “1st half below, 2nd half above” canon. Let’s also point out that it’s kind of funny to call this a “Canon at the Fourth” at all, since the only moment you get a fourth between subject and answer here is when you play a G or a D in the subject. Every other note will have a response that is not a fourth away.

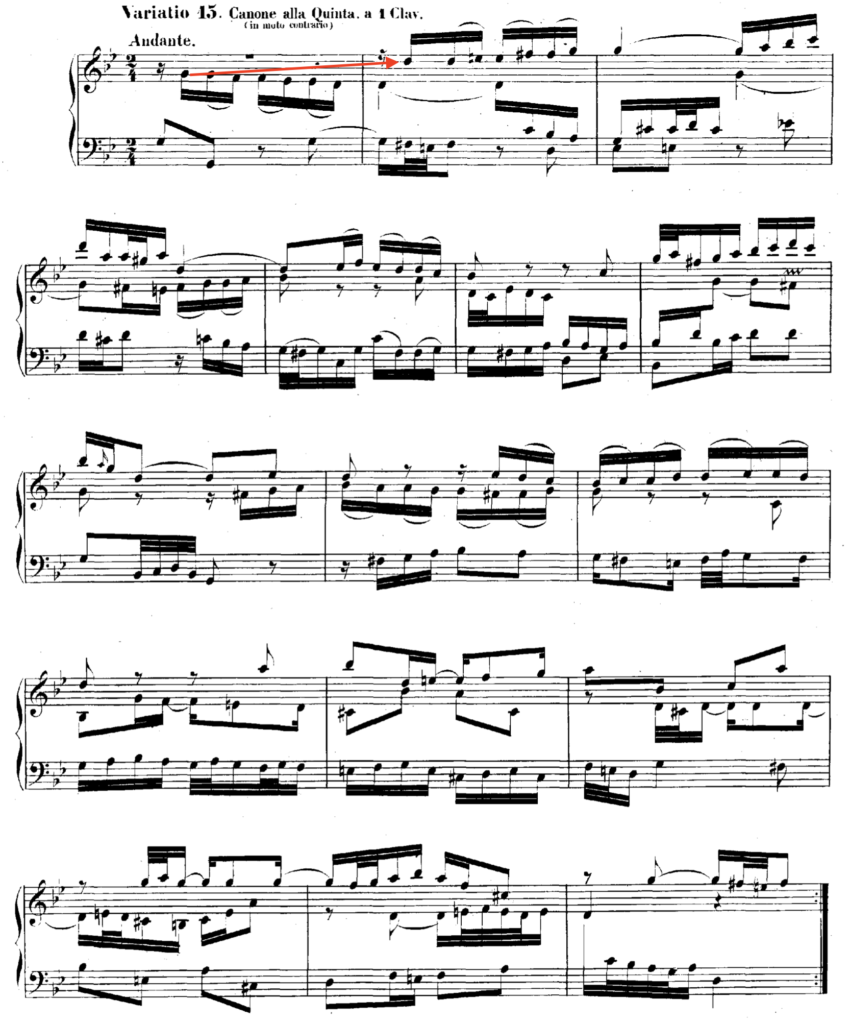

Canon #5, Var 15: Inverted canon at the fifth, with the axis of symmetry between the Bb and B above middle C, so that the G above middle C is transformed to the D above that, a fifth above. The same observations apply here that applied to Var 12. In fact, the two variations are effectively the same canon, in that the same note names are transformed to the same note names in each one, the only difference being the octave in which they are placed (and the minor key of course). Simply because of where Bach decided to place the subject with respect to the axis of symmetry, the subject is 99% of the time below the response, so that I would rate this canon as belonging to the “above” category.

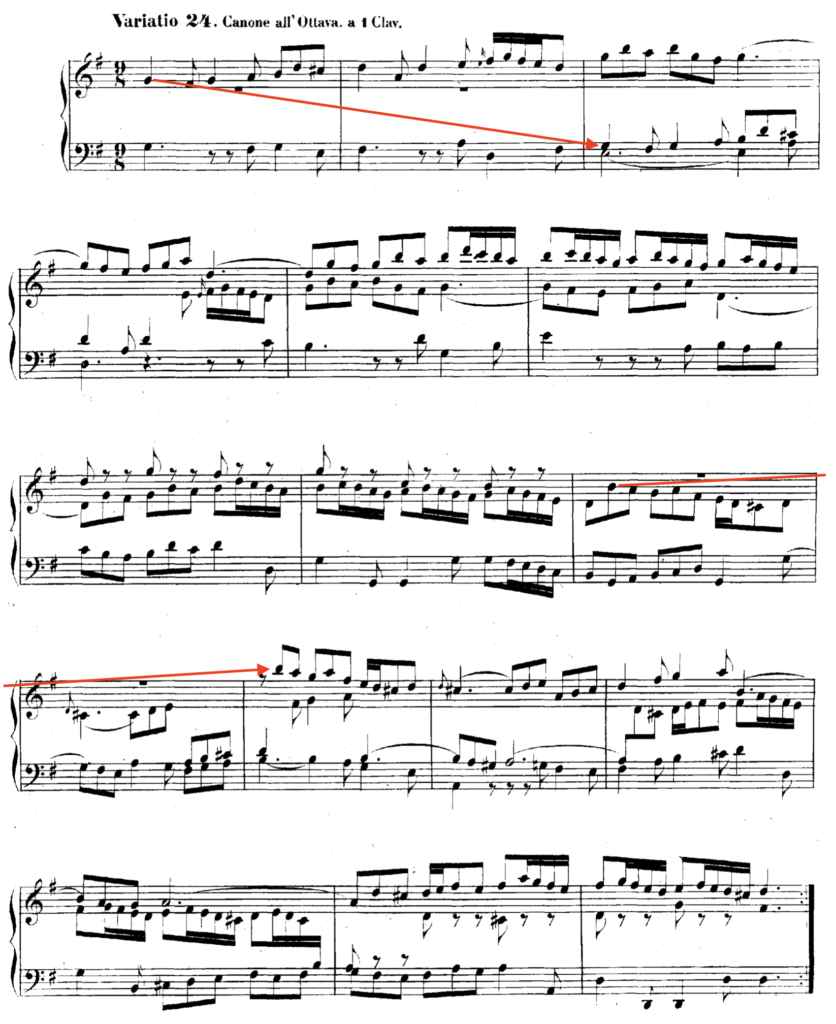

Canon #6, Var 18: Canon at the Sixth —> above

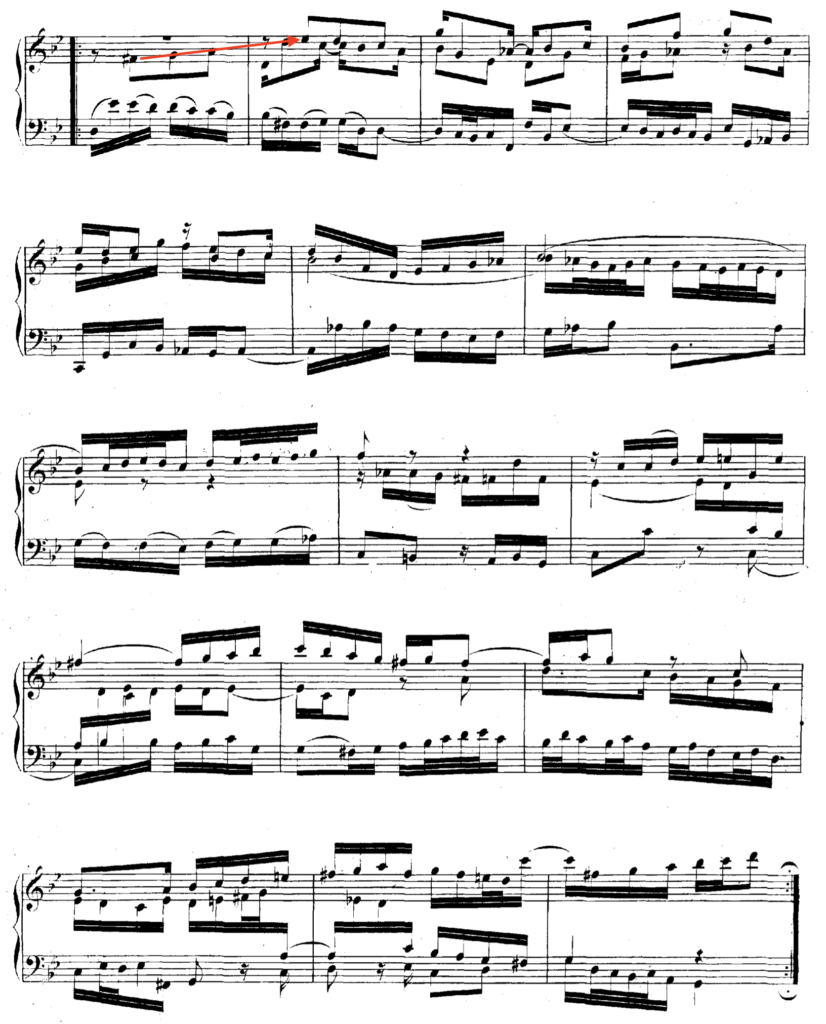

Canon #7, Var 21: Canon at the Seventh —> above

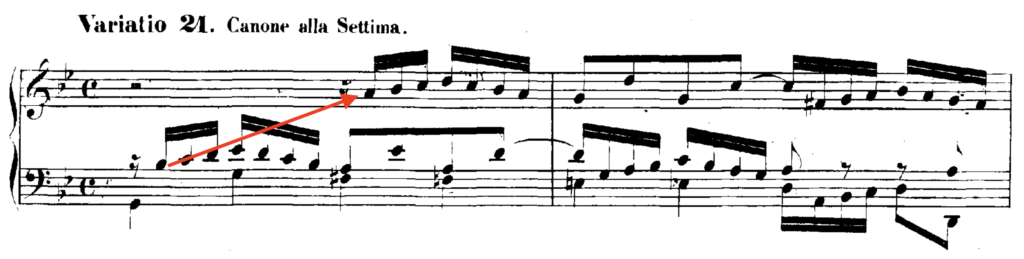

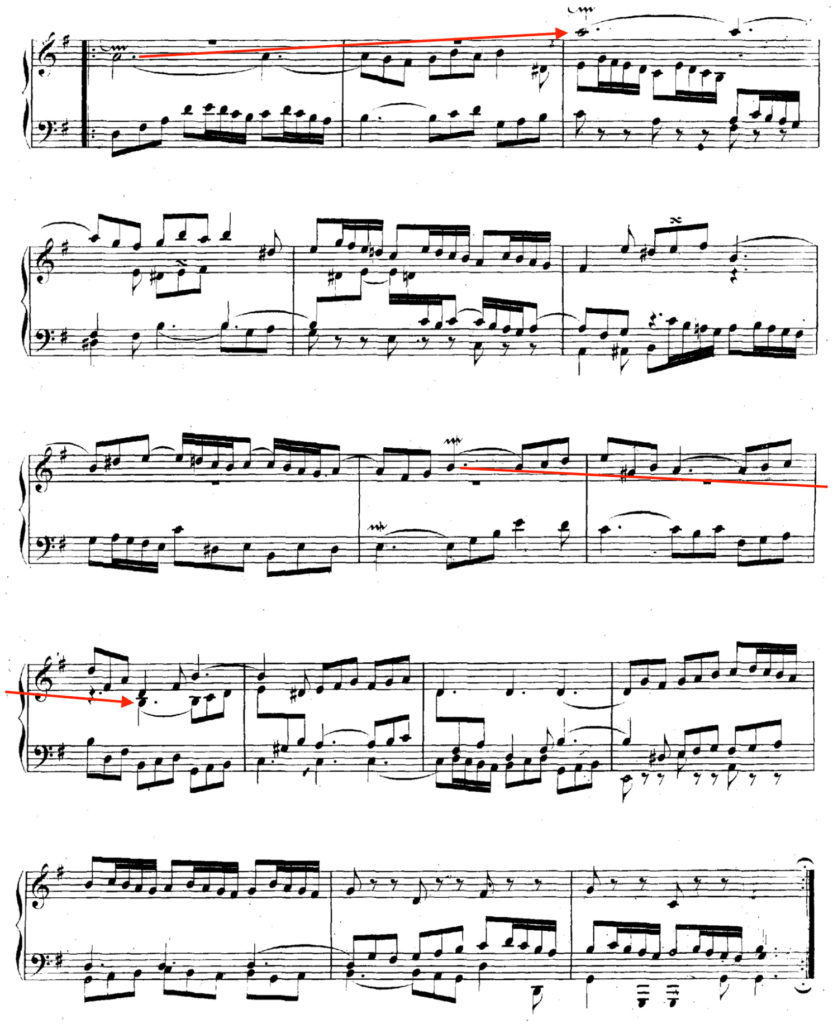

Canon #8, Var 24: Canon at the Octave

1st quarter —> below

2nd quarter —> above

3rd quarter —> above

4th quarter —> below

I love how he switches directions in this one! At the end of each quarter of the variation, the subject becomes non-melodic (the very rare time that this happens in the entire set), with either disconnected eighth notes on each beat, or (at the end of the 3rd quarter) silence. I believe Bach does this so that the change of direction isn’t jarring to the listener. Bach always gets his cake and eats it too — he adheres to the formal logic, but manages it so artfully that it never feels pedantic to the listener.

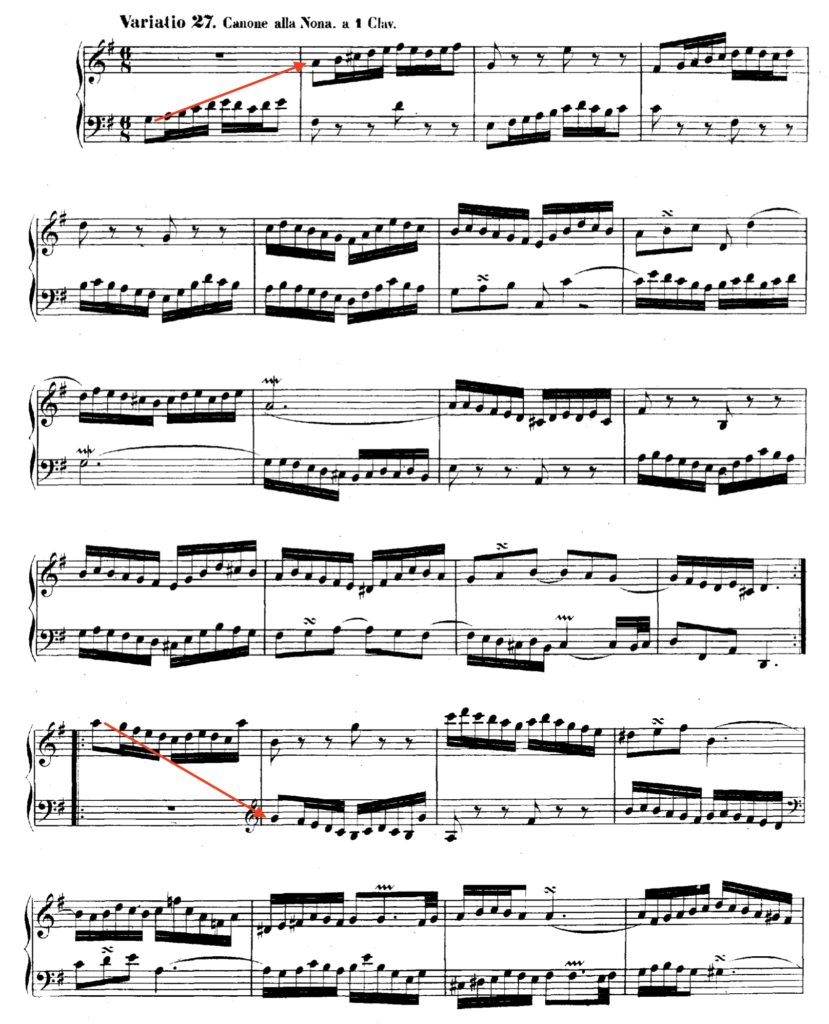

Canon #9, Var 27: Canon at the Ninth

1st half —> above

2nd half —> below

To sum up, we have:

canon 1: no direction

canon 2: above

canon 3: below

canon 4: below / above

canon 5: above

canon 6: above

canon 7: above

canon 8: below / above / above / below

canon 9: above / below

One observation here is that there are what I call “sister” variations. For example, if we ignore octave displacement, the canon at the 3rd is the same as the canon at the 6th, since the first is descending (e.g. G becomes E below) and the second is ascending (e.g. G becomes E above). I’ve already noted that the canons at the fourth and fifth, if we ignore octave displacement, apply the same transformation. We can also observe that the first half of the canon at the 9th applies the same transformation as the canon at the 2nd (G becomes A), and the second half the same as the canon at the 7th (G becomes F). Obviously the canon at the octave applies the same identity transformation as the canon at the unison, and its many switchings of direction seem to go out of their way to stress this point — almost as if Bach wanted to make sure we understood that, on average, this too is a canon at the unison.

So I would pair up the canons this way:

1 & 8: G becomes G

2 & 9: G becomes A

3 & 6: G becomes E

4 & 5: G becomes D

7 & 9: G becomes F

(The canon at the 9th does double sisterly duty. It’s the only canon where the switch of direction actually changes the transformation. This makes it special and, to me, in conjunction with its status as the only 2-voice canon, gives it an air of finality).

Hence the canons of the Goldbergs, ignoring octave displacement, feature not 9 different transformations — or the 7 that you might expect, since if we ignore octave displacement 7 is the maximum that we could have — but only 5. That’s the main point. There are really only five canonic strategies here. We never have a canon at the third above (G becomes B), nor do we have the fifth below or the fourth above (G becomes C). Two of the possible 7 transformations are missing.

Why?

Great to see you sharing your insights here. Having seen a draft of this from last year which you sent me over email, at that time I said I didn’t have anything to add, but now that seems like a lazy answer. As I read it here, I can offer a few additional thoughts to your summary, which is excellent by the way.

To quote from a little-known treatise on canons, “canonic intervals of imitation may be generalised by equating any diatonic interval larger than a fourth with its inversion.” The mirror canons at the 4th and 5th in the Goldbergs do reduce to one process as you point out, and a bit more can be said about this pair of canons in particular, because the reduced process also happens to be the only possible mirror canon in which a tonic triad outlined in a leading voice will be duplicated in the answering voice. Moreover, this interval of imitation answers triads on 2, 3, 4 and 5 with triads of comparable functional weight (7, 6, 5, and 4 respectively). The leading voice outlining a predominant harmony leads to a dominant harmony in the answering voice; that is, 2 -> 7 and 4 -> 5 which are of course strong harmonic progressions. Since 3 is answered by 6, a typical strong harmonic progression such as 1 1 3 6 4 5 1 (Roman Numerals in Major: I I iii vi IV V I) becomes a natural outcome of the canonic process. So it’s no wonder that Bach chose to write these particular mirror canons.

About the canon at the octave (Var. 24). I’d say this one is a series of canons rather than one canon. Where you mention the subject becomes non-melodic, I would say that the subject simply ends. This happens first at bar 7, where the D on the downbeat is the end of the subject, and the following rests and eighth notes are counterpoint against the completion of the canon in the middle voice. The end of the canon is signalled by the rest (since there are no rests in the canon bars 1-6). The following voice includes that D on the downbeat of bar 8 where it finishes the first canon, and then continues as the leader of a second canon. The upper voice answers not on the downbeat (since that note belongs to the first canon) but on the second eighth note, after an eighth rest. A similar process takes place 6 bars into the second half of the piece, where the lower part rests on beats 2 and 3, again signalling the end of that canon, and the last canon begins exactly where that rest would have been in the upper part. (Here there is a small correction to be made in your score: the last arrow there should be pointing from the B in the middle of the measure 1 bar earlier than where it is currently marked.)

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for providing the impetus for me to write these thoughts down! And thanks so much for your thoughts about why the axis of symmetry chosen by Bach for the inverted canons is a special one. Need to dig into this further.

I noticed my mistake in the graphic for Var 24 shortly after posting this, and fixed it, but you beat me to it! Thanks for noticing.

Talk soon!

Dan

PS: Anyone reading this who is interested in counterpoint should check out Andrew’s 24 Preludes and Fugues, written using strict counterpoint in odd time signatures. A fascinating work.