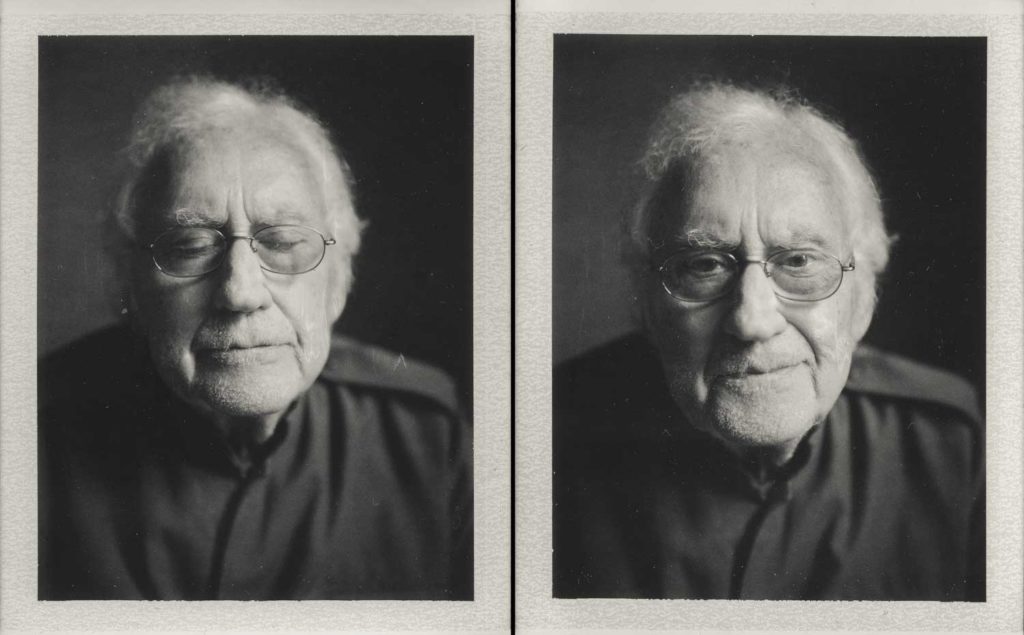

Thanks to JazzTimes for inviting me to write this memoriam. It appeared in their March 2021 issue commemorating lives lost to the pandemic. The photographs are by Josh Goleman, originally taken for our 2018 duo album on Verve, “Decade”.

As someone who likes to think of himself as rational, I can’t bring myself to believe in fate, yet Lee and I seemed destined to meet. Although piano’s been my instrument since I was a child, I had a sax in my teens, and I sound strangely like Lee on home recordings from the time even though I’d hardly listened to him. After I moved to New York in 2006, I put on my mentor Martial Solal’s duo record with Lee one day, Star Eyes, and, moved by a conviction I’ve seldom had before or since — that if I got to play with Lee, I would know what to do — I asked Martial if he would introduce us. Martial gave me his blessing, I went to Lee’s apartment on the Upper West Side, we hit it off immediately on both a personal and musical level, and thus began fourteen years of close friendship and collaboration.

Lee certainly changed my life, but he touched countless others as well during his 92 years on this planet. He influenced the direction of jazz, establishing early on an alternative to Charlie Parker’s brilliant path, even though Lee would be the first to mention that Parker was one of his greatest influences, along with Lester Young and his mentor Lennie Tristano. He studied and learned Parker’s solos, but, when asked how we was able to avoid imitating him and be so singularly himself, even as a 20-year-old in Claude Thornhill’s band, he would jokingly explain that he did in fact try to sound like Bird, but it was too hard.

There may be some truth to this, to the extent that Lee’s shy and sensitive personality was somewhat at odds with the exuberant fire of early bebop. But it obscures a deeper difference of philosophy, which is that Lee, for reasons that remained opaque even to him beyond a deep-seated natural inclination, valued spontaneity at all costs. It’s easy to underestimate how radical his position on this point was: to him, nothing was more important than finding the truth of the moment, and this meant that you couldn’t rely on pre-prepared licks or arrangements. As he travelled the world playing with long-term collaborators or pickup bands (he never hustled for gigs, so he accepted most that came his way), he liked to start from the quasi-blank slate that overplayed standards offered, so that he could jump straight into open-ended exploration. In the 144 or so public concerts I played with Lee all around the world, I must have played All The Things You Are at least that many times with him, but he never played it once the same, and he brought that same spirit of discovery to the free improvisations we recorded on our duo albums. He spoke in straight-forward, unpretentious terms even about profound matters, but he was well-read, and would sometimes quote Heraclitus: “Everything flows… When I step into the river the second time, neither I nor the river are the same.”

Lee’s devotion to personal truth was matched by a tremendous courage. He was unafraid of looking silly, and didn’t hide his vulnerability. Once, with the Thornhill band, he stood up to play a 32-bar solo, and, following his motto “listen is an anagram of silent”, he began by listening intently to the rhythm section to find the right moment to enter. But the rhythm section sounded so good that he didn’t feel the need to contribute anything, and at the end of his 32-bars, he simply sat down again, not having played a note.

Lee’s love of spontaneity manifested in his fondness for animals and little children, who always speak their truth. He would unabashedly greet both on the street, occasionally to the consternation of their minders. But he took music extraordinarily seriously and recognized that it was not enough to be spontaneous; one also had to learn to express oneself with clarity and meaning. “To really improvise, one must be prepared to be unprepared”, he would say. “And that takes a lot of preparation!” His life centered around the search for meaning, and he tried to only make a sound when he had something meaningful to express. In turn, he was an extraordinary listener, constantly searching for meaning in everything he heard from others. Asked if he believed in heaven, Lee said: “Heaven is here, there, anywhere that we can communicate”.

Lee received recognition throughout his career — he was named an NEA Jazz Master in the U.S., a Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters in France and had a street named after him in Italy — but he maintained a disarming humility to the end, never resting on his laurels. He appeared on over three hundred recordings and was loved and respected around the world, but there was never a feeling that he was “great” or that his next gig would be a knockout. Every moment had to be earned and fought for in the present, and failure was always on the table. Till the very end, he simply wanted to make music, and do so as truthfully as he could.

I find this a really wonderful tribute to your late friend and colleague. Today I read it again, because I was checking the origin of a quotation I had written down: “To really improvise, one must be prepared to be unprepared. And that takes a lot of preparation!” Now I am inspired to listen to more of his recordings — and yours! Many thanks.

Thank you David!

Thanks for sharing this great experience

Lee Konitz is a guiding light for me of musical honesty and integrity. You mention 300 recordings? I have about half that many of his, including several with you which I’ve enjoyed and admired. I have written about Lee quite a lot.

https://jmeshel.com/artist/lee-konitz/

🙏🏻🙏🏻

Lee’s passion for jazz was all about the moment, never playing the same thing twice. His refusal to stick to arrangements made him unique and kept every performance fresh. He taught me to embrace change and creativity, a lesson that I’ll never forget. What a guy!