My first project of the 2020/21 pandemic was something I called #BachUpsideDown, an exploration of the sound of Bach’s music in chromatic inversion. During the early months of lockdown, I recorded myself performing the Goldberg Variations as written, and after each variation, I triggered a program I’d written on my computer that played back the notes I’d just performed upside-down. I fell in love with the strange and wonderful sound that results from this process, and decided to make a score so that other musicians could perform the music without the need for special technology. What follows is my introduction to the print edition, which is available for purchase here. You’ll find the YouTube playlist with all 30 variations here, and a May 2020 New York Times feature by Anthony Tommasini here.

Introduction to the print edition

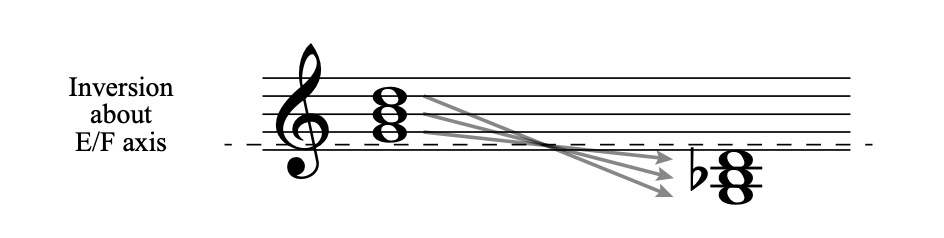

What follows is the entirety of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, published in 1741 under the title Aria mit verschiedenen Veränderungen, but with a transformation: every note of the original text has been chromatically inverted about the E/F axis. In addition, the ornaments that appear in the original as symbols have been written out.

What does this mean? Inversion is an age-old musical process in which musical material is turned upside-down, similarly to the reflected text on the title page of this edition. It does not mean that the music is played backwards, which is a different process called retrograde. With inversion, the arrow of time still points forward, but any motion upwards is reflected to a motion downwards, and vice-versa.

Diatonic inversion

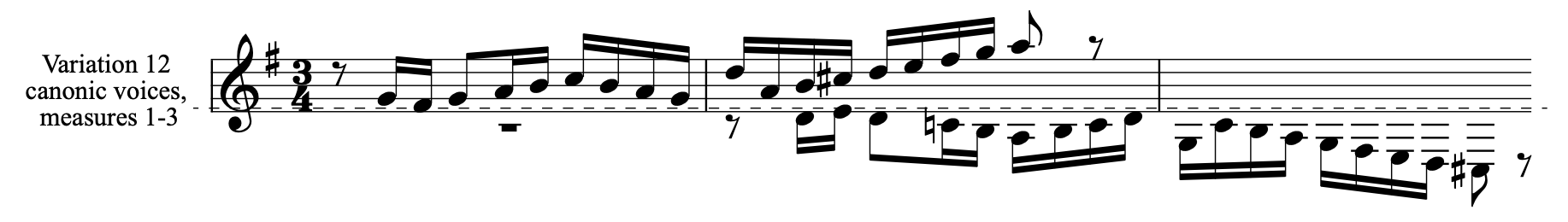

There are two ways of inverting: diatonically and chromatically. In diatonic inversion, the transformation occurs within the frame of a key or scale. We find this type of inversion throughout the original text of the Goldberg Variations. For example, Variations 12 and 15, titled Canon at the Fourth and Canon at the Fifth respectively, are in fact inverted canons. In these two outliers among the nine canons of the Goldbergs, the melody of the initial voice gets inverted diatonically before its repetition in the second voice. In Variation 12, the axis of inversion is between the E and F at the bottom of the treble staff, causing the G at the bottom of the staff to invert to the D a fourth below:

In Variation 15, the axis of inversion is between the Bb and B in the middle of the treble staff:

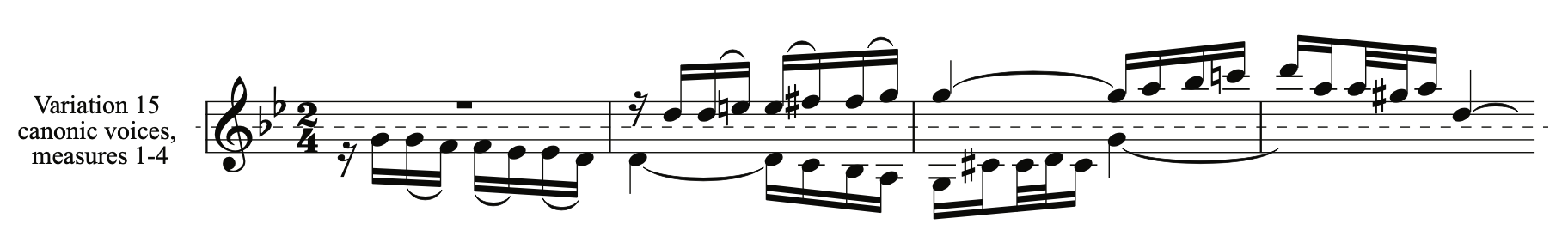

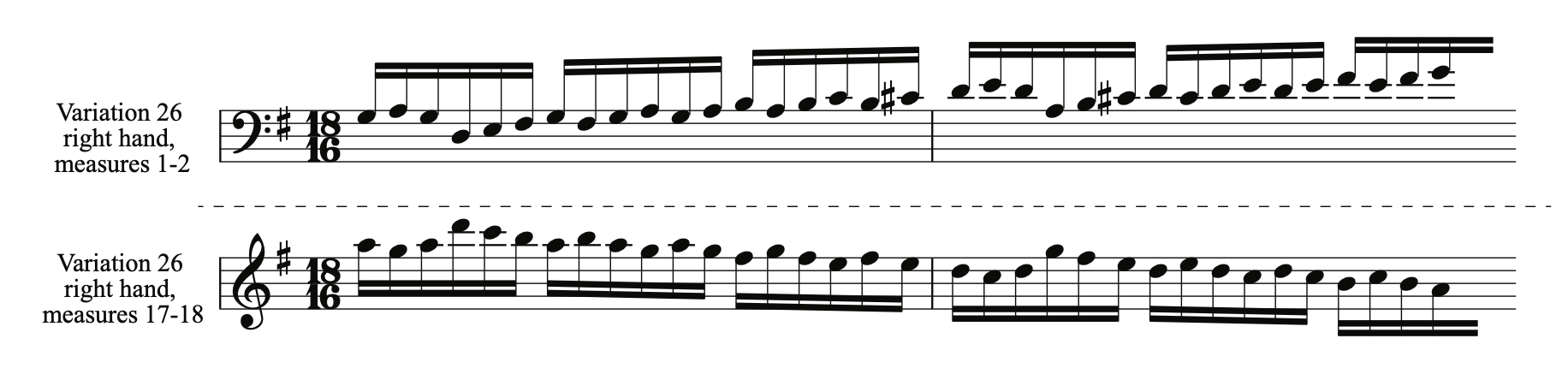

In both these canons, only the G at the bottom of the treble staff — and no other note — generates a response the appropriate distance away (a fourth in Variation 12, a fifth in 15), which makes one wonder whether the titles of these variations are entirely earned. But it’s not only in these two movements that we encounter inversion. It’s ubiquitous in the work, albeit in a less systematic way. In Variation 26, for example, the 16th-note runs that begin the first and second halves of the movement are mirror-images of each other:

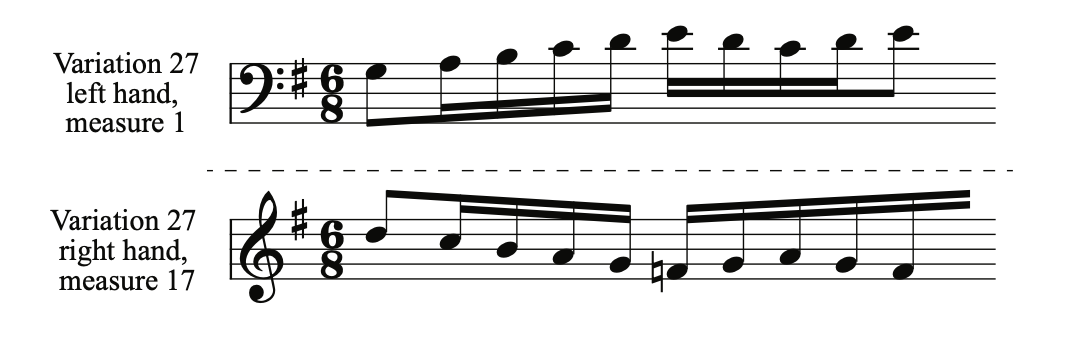

And in variation 27, to choose just one more example among many, the opening canonic voice reappears in inverted form at the beginning of the variation’s second half:

Chromatic inversion

With diatonic inversion, intervals invert to the same interval, but the quality of that interval is allowed to change to fit the local tonality. A major third, for example, may invert to a minor third; a minor second to a major second, as can be seen in the examples above. In contrast, the process of chromatic inversion preserves every interval completely, all the way down to its quality: a minor second always inverts to a minor second, a major third to a major third, a perfect fourth to a perfect fourth, and so on.

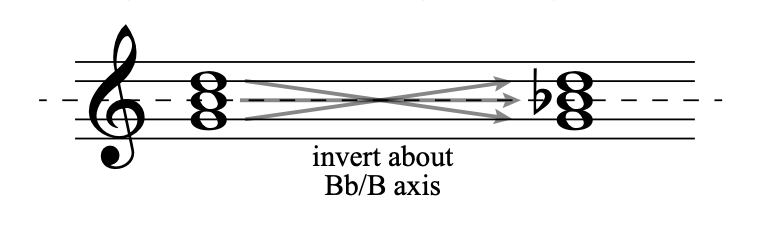

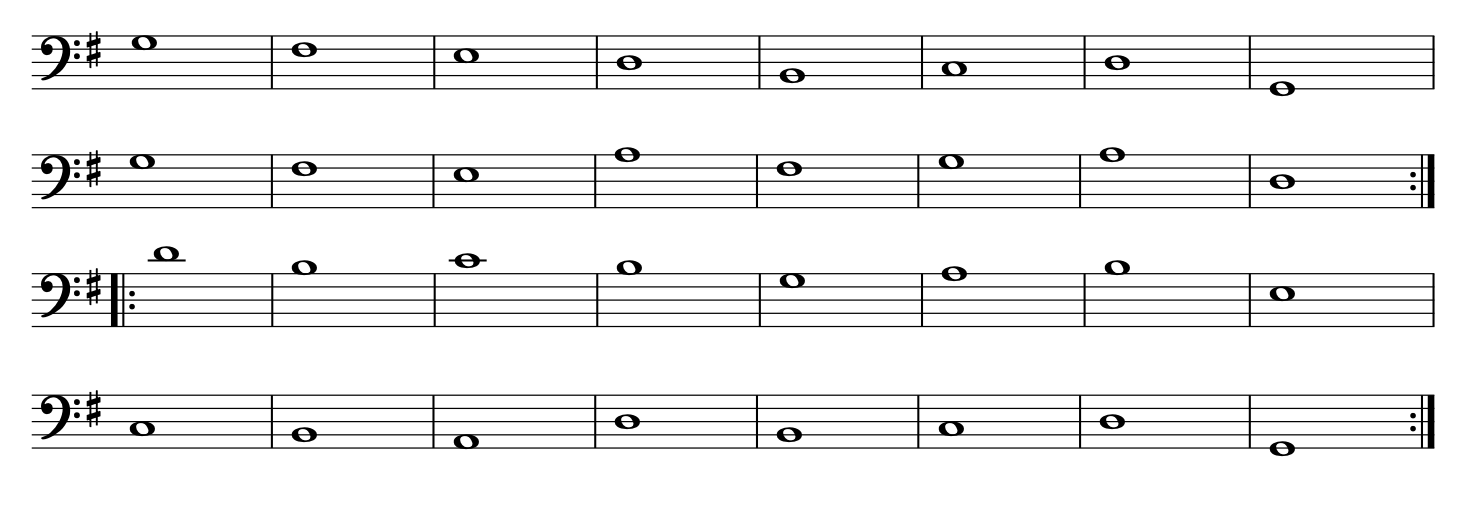

Chromatic inversion operates outside of the confines of tonality; it’s a strict mirroring process with no adjustment for musical context. As we’ll see, there’s no way to preserve the key quality. However, if we choose our axis of inversion carefully, it is possible to retain our tonal center. The Goldberg Variations are in G Major, except for Variations 15, 21 and 25, which are in g minor. Let’s consider our tonic chord, G Major. If we choose to invert chromatically around the Bb/B axis, at the exact midpoint between G and D, then G inverts to D, B to Bb, and D to G. Our G Major triad inverts to g minor:

This isn’t just true for the tonic triad, however. It’s true for the entire key, as can be seen by inverting the G Major scale:

As a result, all twenty-seven variations originally in G major end up in g minor when inverted:

The Goldberg bass line

The Goldberg Variations are built on the bass line and harmonic form of the opening Aria, which itself is an expansion to 32 bars of an eight-bar bass line used by Handel for a set of 64 variations he published in 1733. Bach took Handel’s short phrase and added three repetitions of it, modifying it as he went to move through the related keys of D Major, the dominant, and e minor, the relative minor, before returning to the tonic:

Let’s look at what this becomes when inverted:

The original bass line now finds itself in the treble, supporting the work from above rather than from below. The three modulations structuring each variation’s harmonic form become modulations to the minor subdominant (c minor), then to the relative Major (Bb Major), and finally back to the tonic (g minor). More generally, the inversion process turns perfect cadences into plagal ones, and vice versa. The entire flavor of the work is transformed, even as we maintain every detail of its internal structure.

From minor to Major

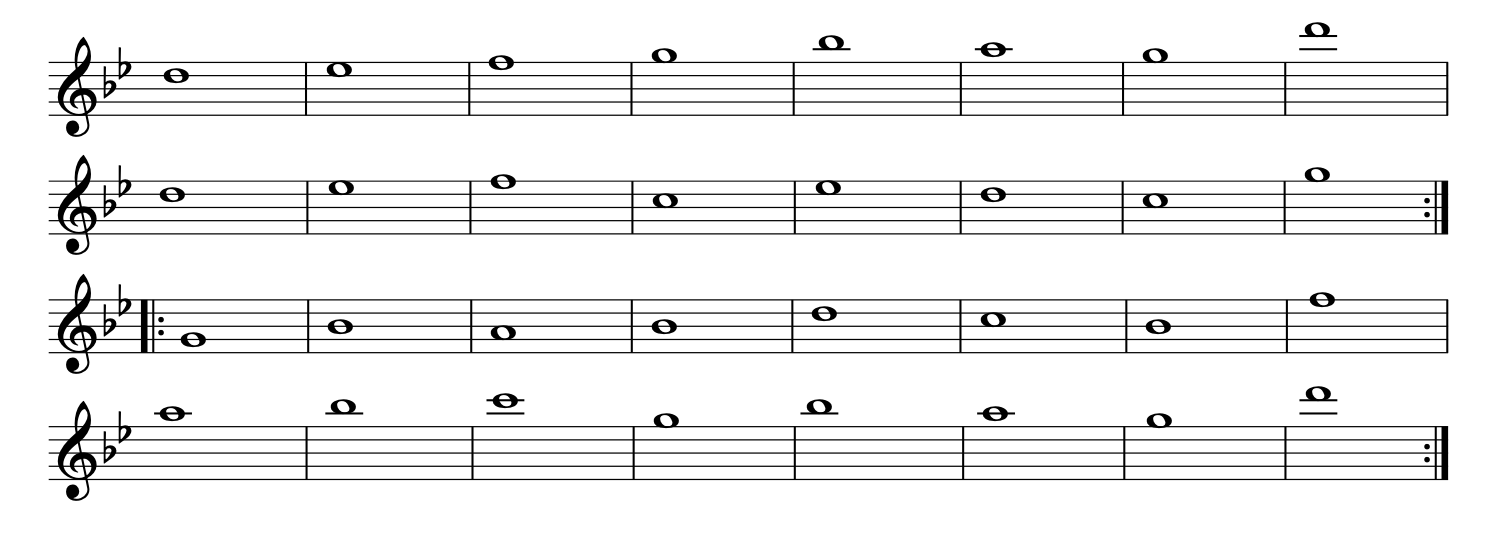

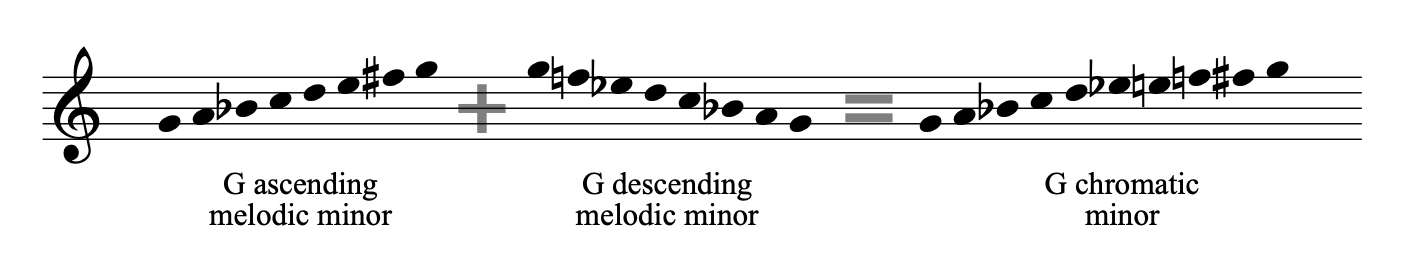

So far, I’ve shown the inversion process going one way, from Major to minor. But the same transformation applies in reverse, of course. Hence, if the major-key variations end up in the parallel minor, the three minor ones are recast to Major. But it’s a very complex type of Major, one with much more chromaticism than we’re used to. Indeed, when Bach and his contemporaries thought of minor keys, they considered both the ascending and descending melodic minor modes to simultaneously belong to the key. This results in the highly chromatic composite mode that gives Bach’s minor-key music its darkness and complexity:

When we invert this mode, we get a version of G Major with maximal chromaticism in the upper portion of the mode:

This chromatic mode forms the backbone of Variations 15, 21, and 25, the only movements to find themselves in the major key when inverted. On the other hand, the remaining major-key variations, originally in G Major and inverted to g minor in this edition, find themselves in a much simpler flavor of minor than we’re accustomed to from Bach, with just seven diatonic notes, the notes of G aeolian, and much less chromaticism. There is a joyful lightness to them as a result.

Axes and tessitura

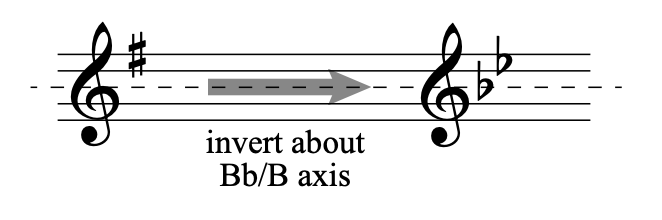

We’ve shown that by inverting chromatically about the Bb/B axis, we maintain our key center of G, although we change its quality. But the same is true if we choose the E/F axis, a tritone away from Bb/B, the only difference being one of register:

This is the axis that I have chosen for this edition, for the simple reason that it’s close to the middle of the keyboard, producing an inversion that maintains most of the tessitura of the original, all while preserving its key center.

One final note on inversion: Bach very often ends his pieces with both the soprano and bass voices on the tonic, which gives a satisfying sense of finality. As we’ve noted, however, in the key of G, the tonic G inverts to the dominant D. Moreover, with inversion, the treble ends up in the bass, and vice versa. So, this final G of the original text, in the soprano voice, becomes a D in the bass voice when inverted. This gives many of the endings here the feeling of asking a question rather than of answering one. One exception is the close of Variation 15, where in the original, the soprano line ends on a high D, with an implication of unfinished business. In the inversion, instead, this high D becomes a low G that gives Variation 15 a rare sense of conclusion, right at the halfway mark of the work.

Ornamentation

And what about ornaments? They’re essential to baroque music, and we find them throughout the Goldberg Variations. To be true to Bach’s careful use of ornaments, which goes beyond mere decoration and often takes on a functional role, it’s essential to invert them along with the rest of the music. To help with this somewhat challenging task, this edition features a written-out realization of the ornaments. A companion edition features the text with the original ornament symbols instead, along with an explanation for how they should be performed.

Counterpoint

What happens to counterpoint when you turn it upside down? Counterpoint is the art of balancing the horizontal with the vertical. The horizontal, in this image, is the movement of notes through time; the vertical refers to the harmonic relationships between notes that sound at the same time. In other words, it’s the art of writing melodies that stand on their own while also functioning well together. In the centuries leading up to Bach’s time, counterpoint became a science, with a system of rules that classified which intervals between notes were desirable (consonances), which weren’t (dissonances), and how one could move elegantly between them.

An essential aspect of counterpoint, from a vertical standpoint, is that it’s primarily concerned with intervals. As we’ve noted, the process of chromatic inversion preserves intervals exactly. Hence, if the rules of counterpoint have deemed a certain passage acceptable, then it should find its chromatic inversion acceptable as well. There is one exception to this, which is that suspensions — notes carried over from a previous consonance which become dissonances when the surrounding notes change — are traditionally only allowed to resolve downwards by step, a kind of acknowledgement of gravity. In the inversion, they resolve upwards instead, in an escape from that downwards pull.

As for the horizontal, consider that it is generally true that a strong melody remains strong when inverted, even though it may be unrecognizable to most ears, and we begin to understand why Bach’s music sounds so surprisingly good when turned on its head: its underpinnings — the forces that make it tick — are impervious to inversion.

Perspective

Why do this at all? Aside from how strangely wonderful it sounds, I believe that hearing this music upside-down reveals something profound about the work. For one thing, it allows us to hear it as if for the first time, a gift when you consider how many times an average music lover has heard the Goldbergs. It’s important to remember that we really are hearing the original work here, in the same way that we are still seeing an original Da Vinci or Picasso if we hang it upside down. It’s only our vantage point that’s changed. It’s easy, for example, to become somewhat blasé regarding the chromaticism of Variation 25 when you’ve heard it many times. But play or listen to it upside down, and you’ll be reminded that this is music that stretches the limits of dissonance in tonality like little else.

Hearing the music this way also allows us to attend to aspects of the music that may have remained hidden to us until now. Bass lines, for example, have a tendency to play a supporting role in our ears. When inverted, they become the main event, the high voice, and as we instinctively bring our attention to them, we are reminded of how much care Bach put into every single one of his melodies, whether hidden or exposed. This is an essential factor in the success of these upside-down Goldbergs: Bach creates all voices equal, with an exceptional symmetry and balance that is undisturbed by inversion. More broadly speaking, it’s a testament to the soundness of his underlying compositional structures that they can withstand this kind of transformation so well.

When I play the music in these pages, it’s striking to me how simultaneously familiar and foreign it sounds. There’s no doubt that it’s Bach we’re hearing, but it’s as if he’d been born not on Earth, but on another planet. Mars, perhaps.

Dan Tepfer, December 2021, Brooklyn, NY

Greetings Maestro Tepfer~

Thank you for your work.

May you have a long wonderfill and awefilled life.

Too kind! Thank you sir!

Dear Dan Tepfer,

A real eye and ear opener. I first studied your analysis and justification and than took to eating the pudding. Wonderful, a deepening understanding of not only Bach’s GV, but of Bach. I wonder what your method would do to the appreciation of, say, Rachmaninov.

Thanks very much,

Koen van Gulik

Does eating the pudding mean you’ve been playing the Variations upside down yourself?