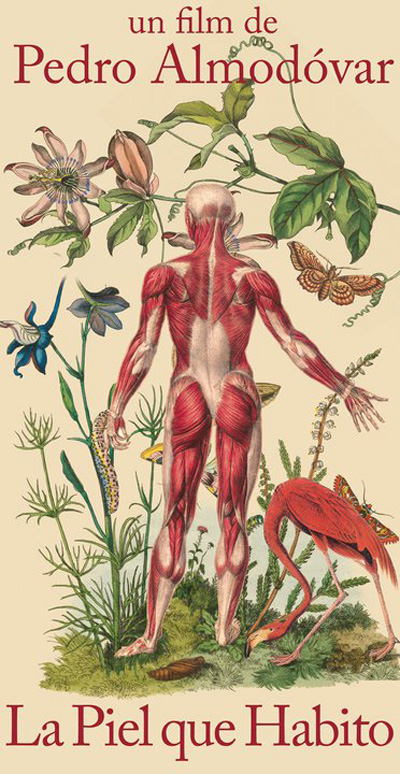

I’m a longtime fan of Pedro Almódovar — it’s hard not to be if you grew up in France — so I couldn’t wait to see his latest film, The Skin I Live In. I saw it last night and there’s really only one word that immediately comes to mind: W•E•I•R•D.

It’s probably the strangest movie I’ve ever seen. Its weirdness is profoundly disturbing because it’s presented in a non-weird package, with Almodóvar’s trademark gorgeous composition and vibrant colors. I’m a fan of strange movies — David Lynch’s Lost Highway was one of my faves as a teenager — but on the weirdness scale, this one takes the cake by a long shot. Usually, the strangeness of a movie is reflected in its form. Black Swan, for example, has all kinds of strange things going on in the presentation that make it clear that you, the viewer, should take everything that you see onscreen with a grain of salt: the form of the film actively reminds you that the story isn’t necessarily real.

In The Skin, the weirdness is pretty much entirely constrained to the subject matter — it’s the story that’s profoundly strange. There’s a little temporal confusion in the middle of the film — it’s unclear whether a flashback actually occurred or whether it’s part of Antonio Banderas’ dream — but that question quickly gets resolved. The film is essentially a straightforward storytelling of a very strange story.

What is this thing, ‘weirdness’, anyway? I suppose the word could describe anything that is disturbing in an unexpected way. A photo of a mass grave in a civil war zone published in a newspaper is disturbing, but it fits into what we know about reality and hence isn’t weird; conversely, most comedy plays on our expectations, and it’s what’s unexpected that’s funny to us, but unless a comic is purposely going for something disturbing (Sarah Silverman?), we usually wouldn’t describe it as weird. But even Silverman isn’t that weird, really, because her comedy fits into a category of cringe humor that we’ve come to expect.

At some level, it’s like the Charles Peguy line, “Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics”, which essentially tells us that you can only be mysterious for a short time — very quickly, the mystery gets dissected and broken down, codified, and soon enough people with power (politics) are arguing about how it “should” be.

It’s the same with weirdness: you only get to be truly weird the first time. In this sense, weirdness is closely connected to newness. Only the new can be mysterious, and only the new can be weird. So it’s really a huge accomplishment when an artist can create a profound, sustained sense of weirdness in a viewer. It’s an exciting feeling, because it means we’re discovering something for the first time.

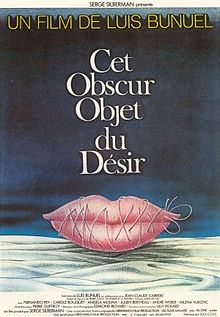

So The Skin has weird content but a non-weird form. This made me think of one of the classic Luis Buñuel movies, That Obscure Object of Desire, which in many ways is the opposite: straightforward content and fundamentally strange form. It’s a fairly simple story of a frustrated love affair, but the woman being courted by the protagonist is played by two different actresses, who look nothing alike, their scenes mixed seemingly at random as the film goes on. In this case the strangeness of the form ends up giving the whole film an unforgettable eeriness that perfectly expresses the protagonist’s frustration at not being able to get any kind of grip on the girl — clearly, he doesn’t even know who she is. You come out of the film feeling like this simple story has been given transcendence by the form; it almost feels like the form has worked its magic in a subliminal way.

So The Skin has weird content but a non-weird form. This made me think of one of the classic Luis Buñuel movies, That Obscure Object of Desire, which in many ways is the opposite: straightforward content and fundamentally strange form. It’s a fairly simple story of a frustrated love affair, but the woman being courted by the protagonist is played by two different actresses, who look nothing alike, their scenes mixed seemingly at random as the film goes on. In this case the strangeness of the form ends up giving the whole film an unforgettable eeriness that perfectly expresses the protagonist’s frustration at not being able to get any kind of grip on the girl — clearly, he doesn’t even know who she is. You come out of the film feeling like this simple story has been given transcendence by the form; it almost feels like the form has worked its magic in a subliminal way.

In The Skin I Live In, you come out of the film feeling that the simple form has made the content feel even weirder. So there may be a kind of a hierarchy here: it’s more palatable to present something straightforward in a strange way than to present something strange in a straightforward way.

Whenever I think about art in any kind of way, I end up asking myself what it means for music. The issue here is complicated by the fact that it’s hard to separate form and content in music (at least with music that doesn’t have lyrics). With most instrumental music, the question “what is this about?” is really hard to answer. The emotional center of a piece — a description of which would probably be the best answer to the question — often emerges as a result of the form. But I will say this: if, when you’re playing an out-there version of a standard, we can say that we’re “talking about the standard, but in a weird way” (which I think makes sense), then if we want to “talk about something weird, but in a standard way” we might be playing a super-dissonant and metrically obscure composition in the style of, say, a polka, no?

And yet for something to strike us as profoundly strange, the way The Skin I live In does, it’s got to be really close to home — to deal with everyday situations and twist them. It’s our attachment to these everyday situations that makes us so sensitive to the twist. In music, it’s harder to say what these everyday situations would be. Clearly we can take elements that have become staples of music — the tempered scale, for example — and turn them on their head — making microtonal music, e.g., but it’s really hard, in music, to summon the disturbing feeling we get when we’re confronted with something that really challenges our morals. Or maybe I’m saying this because I’m so used to strange music — perhaps the people who first heard The Rite of Spring in Paris really were personally weirded out by it? I don’t have any answers here, just a question: what would it mean to make music that feels just as weird as The Skin I Live In? Is it even possible?

Without giving too much away, The Skin makes you think about issues of gender and identity in ways that will most likely be new to you. And in a way, even though it deals with gender at a fundamental level, it’s mostly about identity: the tension of the ending hangs on whether or not one of the main characters has retained the core of her identity or whether she has allowed herself to be made into something else. The ending reminded me of the denouement of Casablanca, where the tension comes from our trying to figure out whether the chief of police is a good or bad guy — first he acts like a bad guy, then a good guy, and we’re relieved. Almodovar takes this one step further: it’s not so much about being a good or bad guy, and more about being true to yourself. After going through so much, do you still know who you are?

Without giving too much away, The Skin makes you think about issues of gender and identity in ways that will most likely be new to you. And in a way, even though it deals with gender at a fundamental level, it’s mostly about identity: the tension of the ending hangs on whether or not one of the main characters has retained the core of her identity or whether she has allowed herself to be made into something else. The ending reminded me of the denouement of Casablanca, where the tension comes from our trying to figure out whether the chief of police is a good or bad guy — first he acts like a bad guy, then a good guy, and we’re relieved. Almodovar takes this one step further: it’s not so much about being a good or bad guy, and more about being true to yourself. After going through so much, do you still know who you are?

I agree that the strangeness of the story at the core of “The Skin I Live In” is amplified by the sheen of normalcy, though I would argue that its telling is not exactly straightforward — we have these casually timestamped flashbacks, and this temporal confusion. Though the questions raised at that point — was it a flashback? was it a dream? — are, as you say, quickly resolved, that momentary confusion adds on to the feeling of unease that builds as more and more about what’s weird about the central story is revealed.

And Almodovar’s fixation on repetitive visual elements and unexplained details, in this particular film, also work to unmoor the viewer. The scene with the hook nose, for example — it’s at once a great sight gag (how silly), delightfully bizarre (how brief, how unexplained) and deeply sinister not just because of any connotations the object itself might have but because of the brevity of its appearance and this lack of explanation. And because it is the one slight change in what otherwise looks familiar, it raises doubt: was it that different? did you really see it? Whether yes or no, that such doubt is raised, at all, is the point.

Thinking about the film now, I’m stuck on this certain, queer flatness to the main characters of the doctor and Vera. Manohla Dargis, in her New York Times review (have you read it?) says Vera is “largely opaque” while the doctor always feels “at an arms length”; for story purposes, the characters can only be so developed or unveiled. You can only really figure them out to a degree. The characters are mostly vehicles for the story, for the film’s meditation on, well, the skin one lives in. And I think this necessary mystery results in a relative weirdness — weird for Almodovar, because of previous films that are built upon characters.

When you ask what would it take to make music that feels as weird as this particular Almodovar film, what do you mean by “feels”? Because I think part of the weirdness of “The Skin I Live In” is the very physical, tangible unease it creates in the viewer. Certainly there is the psychological weirdness you contend with while considering the questions of gender, identity and the physical self that the film asks you to consider. Weirdness to think about. But there is, too, some sort of visceral, bodily response that I have a hard time putting to words. I loved the film. I would say that I enjoyed watching it. But I don’t think there was ever a moment in the theater where I wasn’t incredibly tense. (Forgive my double negative.)