(Cross-posted from UCLA’s Ethnomusicological Review. Thanks to AJ Kluth for inviting me to write this piece for the journal.)

As I look back over the last ten years and the peculiar journey with J.S. Bach that the time represents for me, it’s sometimes hard to believe that I’m here, now, playing the Goldberg Variations from memory in their entirety, for sometimes sizeable audiences, well enough apparently to get enthusiastic approval from the classical section of the New York Times. I’m really a jazz pianist, after all, and the Goldbergs are hard. And the crazy thing is that I never set out to do this in the first place. How did I get here? The best answer I can give, to echo an experience many musicians have reported through the years, is that Bach taught me.

I grew up in Paris, France, in an American family, and started studying piano at the local conservatory when I was six. I was never asked what I wanted to play, as some of my friends in the US were—playing TV themes wasn’t on the radar. Mostly, I was made to play Bach, lots of it. At the same time, following the example of my grandfather, a jazz pianist on the West Coast, I started improvising, and that mode of music-making quickly took over my fledging artistic identity, even as I kept going through the classical repertoire with my teachers at the Conservatoire.

So I grew up with solid classical training paired with an all-out obsession with jazz and improvisation, which I mainly taught myself. In my early teens, I discovered the Goldberg Variations at a friend’s house in Paris, as recorded by Glenn Gould in 1981, and they took hold of me then like the most beautiful and tenacious earworm. Still, it was only in my early twenties, while studying jazz at the New England Conservatory, that I got a score, and even then, it took me a long time to look past the Aria. Slowly, out of what felt like simple curiosity, I started learning a Variation here and there, in breaks between practicing jazz scales. By the time I moved to New York, in ’06, I had learned the first five, at most. And yet, even as I put all my efforts into breaking into the New York jazz scene and developing a personal voice as an improviser, the Goldbergs stuck with me. I kept coming back to them, and found a classical teacher, Zitta Zohar, who convinced me they were somehow within reach.

The jazz pianist Fred Hersch, a long-time mentor of mine, recently reminded me that he had asked me, back then, why I was spending so much time learning the Variations, music that I would presumably never perform. Apparently I answered, “I don’t know—it just feels like something I have to do”. And so I soldiered on, slowly and not all that surely.

Meanwhile, my jazz career was developing. I got a boost from the American Pianists Association’s Cole Porter Fellowship, a competition prize that included a fair amount of touring. And so it was that I found myself backstage at a small concert hall in Czech Republic in early ‘08, fifteen concerts into a twenty-day solo tour, nearing creative exhaustion. I had decided for some reason that the gigs should be freely improvised, and I was starting to run out of ideas. So I decided to use the Goldbergs as inspiration: I played the first four or five, and followed each one with long, freeform improvisations that used the spirit of the preceding variation as a jumping-off point. The audience’s reaction surprised me—I walked off stage feeling that something special had happened. So I tried it again the next night. Bach’s genius suddenly struck me hard: instead of panning for gold dust in a cold and barren stream, which is how it increasingly felt to make improvisations up out of nothing, using the Goldbergs as inspiration was like starting with a giant gold nugget in my hand. Each one had such an utterly distinct identity. Suddenly my improvisations, though still totally speculative and fanciful, had as their subject something very specific, something rock-solid and strong.

And so my improvising started to teach me about Bach. Back home, as I turned to him again with renewed enthusiasm, I wanted to know why it was that each of his short pieces felt so entirely of a piece. The answer—Bach’s extreme compositional economy—took a long time to reveal itself to me; strangely, it didn’t jump out at me at all when I was just learning to play the pieces. And yet, to take an early and simple example, Variation 2 introduces a motive in its first half that gets repeated nearly verbatim in every single bar of the second half, this motive itself being derived from the oscillating bass-line figure that repeats throughout. I can only describe Bach’s strategy for saving the piece from predictability as sleight-of-hand: like a skilled magician, he continuously directs our attention away from the obvious. The clockwork machinery hides in plain sight.

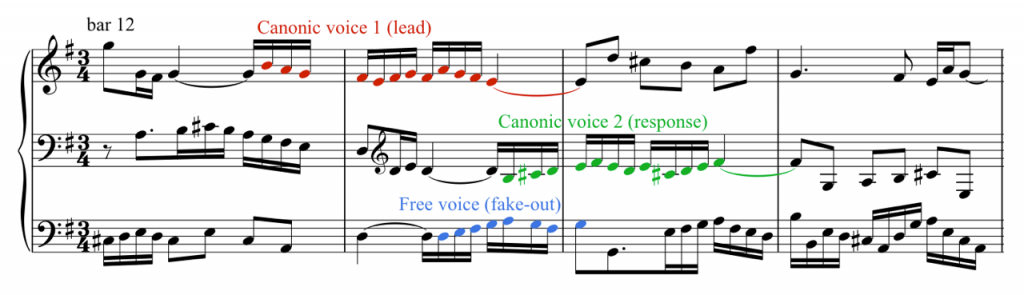

He uses misdirection throughout the Goldbergs, in fact. Where a lesser artist might have wanted to make his achievement in devising a series of canons at every interval from the unison to the ninth clear to the listener, Bach often seems to do everything in his power to hide it, even as he never breaks from strict canonical form. Besides the continuous overlapping and crossing of voices, which is its own form of disguise, there’s a wonderful moment in Variation 12 where the third voice, which is free and not subject to canonical rules, steals the thunder from one of the 2nd voice’s entrances by playing its melody a third away, a beat early.

Only the least pedantic composer would do such a thing. And this is in a canon at the inverted fourth, where a listener’s chances of anticipating the canonic response are even lower than in the non-inverted ones! An advanced volleyball-like fake-out is being deployed against an opponent who couldn’t possibly return the ball if he tried. Bach, I slowly realized, had his cake and ate it, too: his structures, if you look, are as plain as day and as solid as the steel skeleton of a modern building, and yet we rarely, if ever, notice them (as we often do, for example, in Handel). We only hear the incredibly expressive melodies, the rhythmic inventiveness, the continuous small surprises. Has a rule-follower ever been less boring than Bach?

By the summer of ’09, I had worked up enough courage to play eight of the Variations, followed by improvisations, at a small solo concert in Paris. I had been studying Zen philosophy and believed wholeheartedly that an improvisation should have integrity, as a piece of music, if I only put myself in an unobstructed frame of mind and let it flow, as it were, out of me. And the audience, for the most part, was convinced—it felt, again, like something special was happening, that I was exploring fertile ground.

But something started to gnaw at me: was it truly right, when Bach was being so phenomenally economical and elegant, to respond in such a freewheeling way? What would happen if I started to borrow some of his structure, too, beyond his emotional leads?

In the fall, I had a small solo tour through the Midwest, and played the Goldbergs on every gig. This strange idea—of following one of the most perfect works of art with quite imperfect improvisations—was starting to crystallize in my mind as something that had a certain legitimacy, partially as a result of personal conviction, but also because of the encouragement I was getting on the road. (I would later learn that the idea of improvising off of the Goldbergs wasn’t new: John Lewis and Uri Caine, among others, had recorded their own treatments of the theme in different ways.) Still, a year went by before I started thinking seriously of recording it. In early ’11, after releasing a jazz piano trio album of original material and writing a concerto for piano and wind symphony, I happened to meet Bonnie Barrett, the director of Yamaha Artist Services in New York. I became a Yamaha artist and saw an opportunity: if I brought in my own recording gear, I could use the Yamaha showroom in Midtown Manhattan to make my solo record with virtually unlimited studio time. As much as I’d been performing the music in public, a part of me realized there was still a lot of work to do. I just didn’t know quite how much.

To make a long story short, I recorded what eventually became Goldberg Variations / Variations three times. Once as I’d been performing it, with fewer than half the Variations and long, rambling improvisations. Then, when I realized presenting only part of a work so whole as the Goldbergs to the world would be an embarrassment, as a much-too-long and obscure investigation into all the Variations, with a non-linear structure and a speculative tone throughout. And finally, once I realized that the purity and coherence of the Goldbergs called out for the most simple and clear structure possible, the way it finally ended up, with each of the 30 movements alternating with an improvisation of similar length, closely linked to the preceding Variation.

Since I essentially learned to play the second half of the Goldbergs while I was recording it, I started to think of the project less as a record of a live performance and more as a conceptual work that might end up only existing as a recording. There are, after all, many electronic and pop artists who never perform their work live. Recorded music can be a destination of its own.

The recording process was a powerful learning experience for me. Suddenly my weaknesses of articulation and phrasing, when I played Bach’s notes, couldn’t be ignored (as they could so easily when I practiced at home, or even when I performed). Alone in the Yamaha space, often late into the night, I recorded take after take of the Variations, and didn’t shy away from editing the best portions together. Glenn Gould did plenty of editing, I reasoned, so why couldn’t I? (I conveniently ignored the fact that he, at least, was more than capable of performing the work in front of an audience.) Similarly, the recording process brought out all the structural, emotional and technical faults of my improvisations. It became clear to me that the only way they could hope to stand up next to the beauty and perfection of the Variations was if they lost most of the indulgence I’d been allowing them to have. They needed to be concise and focused; they needed to get to the point, all while remaining personal. I started to develop explicit strategies. I realized, for example, that I was capable of improvising my own canons, as long as I kept them fairly rudimentary. I realized that many of the virtuosic Variations stemmed from a very restricted amount of material, and tried to find ways to improvise with a similarly limited set of ideas. I saw that Bach gave himself considerable license in the way he navigated the I-I-V || V-vi-I harmonic framework that all the Variations share, and let myself take my own varied pathways through the changes. I researched the last Variation, the Quodlibet, learned the words to the folk songs it uses as its melodic material, and substituted two jazz tunes I love as material for my improvised response. I gradually went from an implicit, alchemical relationship with the Variations to a much more precise and explicit one. And to my surprise, I gradually saw the project turn into something that felt like it had an integrity of its own.

It’s hard to record improvisations. There’s always the possibility that the next take will be better—it’s hard to stop. And yet as I recorded and re-recorded my responses to Bach, I began to recognize a flag that would occasionally go up in my mind, on good days, saying “this one’s good enough”. At first it was only one of my improvisations that felt that way, but I knew I had found a tone that rang true. My goal became to extend that tone, that feeling. I found it in another, then another, and later, in most of them (but not quite all). Saxophonist and producer Ben Wendel came in to help me choose the final takes, and suddenly I had a 62-track, 78-minute solo piano record that didn’t fit into any record-store genre category.

When it came out, at the end of 2011, I figured I would play a couple CD-release concerts and get back to touring with my trio or playing duo with saxophonist Lee Konitz, with whom my musical relationship had been growing. But to my surprise, critics either absolutely loved it (many of them) or loathed it with a passion (a few of them), and it started to take on a life of its own. After the Wall Street Journal ran a smart and generous feature, it even—surprisingly—started to sell.

For the album release, I played the full first half of the Variations for the first time, from memory, and it felt like the hardest thing I’d ever done in my life, like teetering on the edge of a precipice from beginning to end. I played the Paris CD-release gig at the Sunside, a small jazz club, and an agent heard me there who decided to take a chance on me. Soon he had booked a long fall tour for me in surprisingly large venues in France, and it dawned on me that it just wouldn’t be good enough to play only half of the record. I traveled to Cuba and for two and a half weeks studied percussion in the morning and memorized Goldbergs in the afternoons, away from cell phones, internet and acquaintances. An inexperienced performer of classical works, this was slow work for me, but I found it intensely rewarding. The act of memorizing forced me to make sense of the Variations, to organize them in my mind in a way that I hadn’t had to in the recording process. Bach’s economy became all the more apparent, as did the many-fold symmetries that govern the entire work, from the structural to the physical.

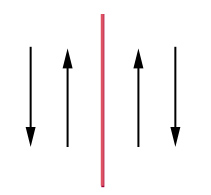

Bach was a lover of symmetry. If most of us can agree that symmetry is important in aesthetics—people tend to prefer symmetrical faces to asymmetrical ones—Bach took the idea to the extreme. At the physical level, in almost every variation as well as the majority of his other keyboard works, both hands get treated with exacting evenness, as if he wanted the interpreter of his music to fully appreciate the symmetry of the body, from the hands to the hemispheres of the brain. It’s not so much that the music is equally difficult for the left hand as it is for the right, although that’s part of it: it’s that to play Bach’s music well, one is obligated to bring the same amount of melodic consciousness to the left hand as the right. This is not the case in keyboard music by most other composers, which tends to heavily favor the higher register of the right hand. I’ve always resisted redistributing the voices of the Variations between the hands for this reason, even though it’s fairly common practice to do so in order to reduce hand crossing. To me, the feeling of bodily symmetry is an essential part of the experience of playing the piece.

At the structural level, the Goldbergs exhibit symmetries from the smallest to the largest scales. At the smallest, Bach is constantly playing with inversion, one example being the 16th-note runs that begin the first and second halves of Variation 26 above, strict mirror-images of each other.

At mid-scale, the rising or falling direction of the canonic intervals offers its own symmetries. Variation 24, for example, starts as a canon at the falling octave, switches to a rising octave on either side of its middle, and ends at the falling octave again, showing palindromic symmetry in its structure.

At the largest scale, the I-V || V-I binary form of the Aria and the Variations, with its central axis of symmetry, reflects the symmetry of the whole work, which similarly starts and ends in the same place (the Aria) and is split at its midpoint in the silence between the 15th variation and the 16th variation, the only to be titled “Overture”—a new beginning. The division of the Aria into 32 bars similarly reflects the work’s division into 32 movements, connecting the part to the whole. It’s easy to see this as an analogy of our existences: from ashes to ashes, with life in between. No wonder, then, that the Goldbergs are often described as expressing every possible shade of human emotion.

By the fall of ’12, I had coerced so many friends into letting me run through the program for them at home in casual performances—always with their share of little disasters—that I was beginning to get an idea of what I was up against. Performing the Goldbergs in public is not only a musical and spiritual challenge; it’s a physical and mental marathon, too. There’s no place to hide in Bach’s limpid music—it will immediately reveal and magnify any lapses in concentration, any tightening up of the body, any fear. And alternating between my role as interpreter of the written text and my role as in-the-moment improviser only made the task harder, constantly jolting me out of the possibility of getting ‘in the zone’ as I switched between mental states. To say I was terrified is an understatement, but the truth is that I’ve always been a thrill-seeker, in sports just as much as in music. So the terror had its own attraction. My dad called me an adrenaline junkie. And I think it’s fair to say that it’s during the fall tour that I started to learn what it really means to perform the Goldbergs in front of an audience. The tour was well received, but after I came home to Brooklyn, I heard Piotr Anderszewski play Bach’s English and French Suites at Carnegie Hall and was struck with a mirror-neuron-like physical feeling for how direct and unencumbered his relationship to the piano was. I realized that I had only fleetingly truly relaxed my body into the keyboard when I was playing Bach’s music on the road. A number of people had noted, in fact, how different my body language was between the Variations and my improvisations. The fear of a memory slip or technical slip-up kept my body on edge.

Much of my work since then has been on diminishing the sensation of fear. I realized, for example, that focusing my attention on rhythm and how it manifested in my body was a big help. It gave the notes a context to sit in and directed my attention forward, slightly into the future and away from the paralyzing present. I also realized the obvious, which is that the more I deepened my knowledge of Bach’s text, the more confidence I had when presenting it to an audience. Weeks after a solo performance in Vancouver, on the tail end of a duo tour with Ben Wendel, with whom I had just released a duo record, I got a call from an accomplished baroque harpsichordist who specializes in Bach and had heard my concert there. While he wished me good luck, he told me in no uncertain terms that my performance of the canons needed work. Why would you only bring out the top voice, he asked, when they’re all equally important? I didn’t have the heart to explain that I’d bring them all out if I could—that I was holding on for dear life out there. But I did take his cue and returned to Bach’s score with increased humility, practicing singing the interior voices of the canons while I played the others on the piano, or at other times willing myself to transpose variations to foreign keys from memory, and again at others spending hours obsessing over the exact phrasing of one short melody. Every time I opened the score, I was reminded that there is always something further to discover in Bach’s music—that the more you seek, the more you find. One thing dawned on me: when you’re starting with material of this quality, you don’t need to add anything to it. Your job is to get out of the way, to solve your interpretive problems so as to reveal the work itself as clearly as possible, like scraping mud off a diamond. I’m grateful to the pianist Simone Dinnerstein, a masterful interpreter of the Goldbergs, for generously giving me encouragement and musical advice during this time.

In the fall of ’13, a short solo tour came together on the East Coast, culminating in a show at one of my favorite New York venues, Le Poisson Rouge, a place that will present just about any style of music, from Johnny Gandelsman on solo violin to Laura Mvula with full band, as long as it’s good. Something happened on the tour—something started to click emotionally. I stopped trying so hard, started to let things be, both in the Variations and my improvisations. “Don’t try to make the music beautiful – it is beautiful; just let it out”, the beloved piano guru Sophia Rosoff had told me, and I slowly began to understand what she meant. And after the gig at Le Poisson Rouge, a man introduced himself to me, warmly, as Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times. A day later there was a glowing review in the paper, and suddenly the record was selling better on Amazon than Justin Timberlake and Lady Gaga, if only for a brief while. In the following days I got calls from some of the best presenters and festivals in America inviting me to perform.

What astonishes me about this is that the same critic, a fierce and erudite expert on classical music, may very well have panned me if he had heard me two years earlier. It took me that long to even begin to understand what was at stake when performing this music in front of an audience. And in those two years, my rising standards for what makes an acceptable performance of Bach started to spread laterally to the other types of music I was making, from my composing to my improvising. Dealing with Bach so frequently and—it felt—so intimately made all but the most well structured and meaningful new music feel lacking in comparison.

Looking back, as I prepare for solo shows at the Ravinia Festival, SF Jazz Center and Wigmore Hall in London, I’m amazed any of this happened at all. From many perspectives, I’m sure it would seem that I developed my Goldberg Variations / Variations project exactly backwards. But I didn’t know any better, and that’s probably why it ended up coming into existence—I just followed my nose. Above all, I’m grateful for the opportunity, a truly unexpected one for me, to engage much more deeply than I thought I ever would with one of music’s greatest geniuses, and to let Bach teach me.

Dan, thank you for such a great story. It teaches a lot.

Thanks much, Lena, for taking the time to read it.

Honoured to have met you, heard your performance in Vancouver and had an opportunity to discuss with you some of the facets of Bach’s wonderful music; there’s always so much more to discover!

Hope you can make it back this way again soon … N

Thanks so much, Nou. You’re part of this story too. Have very fond memories of our talk together before the Vancouver show. Hope to see you again soon.

I’m so impressed with your writing as much as your playing the Goldberg. Hope to see your performance some day!^^

beautiful essay Dan… Amazing stuff. Almost as good as your Goldbergs! Always been a huge fan since the beginning

Right back at you, Alessio! Honored to know you. Thanks for the inspiration and the support over the years. See you soon!

Dan, I heard you play the shortened version of these a few years back in Ann Arbor, and our collective jaws were on the floor from beginning to end. It sounds like you have continually evolved this project, and it will bear repeated live listenings. Can’t wait to hear you play them again. Best to you.

Hi Andy, I remember that gig well. Part of the short solo tour through the Midwest I mention above. There were maybe 12 people in the audience? But very nice vibes, and a great piano. An important step on the journey, for sure.

Yes, I couldn’t believe there were only 12 people there, which is a crime. The piano is a German/Hamburg 8-foot Steinway.

Well, I was happy to be there at all, 12 people or no people… So thanks much for being there and for taking the time to read this, Andy.

Dan – unfortunately I was unable to hear more than about 1/3 of your comments at the Community Music Center Friday night…. even with hearing aids. You are somewhat soft spoken, and you weren’t provided with a mike, which I would suggest in settings like that.

Saturday night was quite different. Usually in music presentations there are periods where one can momentarily relax — Saturday was not one of those times. Even when you were not playing the anticipation of the next note was intense. I’ve been to many many piano concerts, but only once could I use the words throbbing excitement to describe what I heard. That once was in 1952 in New York hearing Art Tatum.

You are amazing

Norm

Thank you, Dan Tepfer. It was beautiful…

The words/writing above are, for me, the literary form of the musical form that I heard and saw in your San Francisco, Jazz Center, Nov., 2014, performance. I was there as a person who loves music, but also as an actor/director, listening, watching, feeling… with you as pianist/jazz pianist who knows, loves and plays music…classical and jazz,

I am, one, for whom the ACTION (inner, motivated action) of the play necessitates that the whole person –mind, body, emotion of the actor– be ready, used, having been prepared, and then released, in the character’s moment of playing, in the giving and receiving of the ACTION with the other actors, to create “ensemble performance” for the audience, of the playwight’s dramatic meaningful intention/Action. This is what you did for Bach’s classical, and Tepfer’s jazz music and playing that was so beautifully one, complete –Now, and your own.

When next you come to SF, I would like to take you for coffee afterwards,

or sometime during your stay, if possible, to talk with as a theatre person… gm

Thank you George! I love thinking of acting as an analogy for music-making. Thanks for your generous comments — so glad you enjoyed the SF show.

PS— on the topic of acting, you might find my latest post on the movie Birdman interesting!

Dan, I heard you the other night in Cleveland, after which I asked you how you came to the Goldbergs. You recommended this item on your blog. Thanks for doing so. It’s a fascinating read about an intriguing and what must have been intensely enriching personal quest: like a textbook case of finding higher consciousness levels through creative struggle. The pay-off is clearly heard in your fine work. Your recording draws me back again and again, especially to hear the unique suspensions between Bach and jazz that you bring to your “Variations”. Even if only vicariously, listening to them makes me feel as though I’m on a similar creative journey.

Dan, thank you for such insights into many things – especially your personal journey of performance practice, and also “how Bach works”. I love that you make Bach relevant to today’s music, in new and surprising ways.

So now I’m listening to your SoundCloud posts, and enjoying some “algorithmic tran[s]formations”. But I’m puzzled by the title of the first – how can an algo trans also be an “improvisation”? Or maybe the impro was the germ that seeded the transformations …

Hi Yahya,

Thanks so much for this! I’m glad some of this spoke to you. And great question regarding the first movement of Algorithmic Transform. It’s a transcription for orchestra of an improvisation I did with an algorithm. In other words, I programmed a computer algorithm that responds in real time to my improvisation; so naturally I respond to it, too, as I improvise. NPR made a beautiful video about this project last summer: https://www.npr.org/2017/07/24/538677517/fascinating-algorithm-dan-tepfers-player-piano-is-his-composing-partner

Be well! Dan

Pingback: Melhdau, Tepfer and Improvising on Bach – The Necessary Blues